NIH Funding Extends Cameron Lab Research on Disease-Causing Misfolded Proteins

The National Institutes of Health is again supporting the significant work of Ursinus Professor and Chair of Biology Dale Cameron and students in his lab with a $418,000 competitive grant renewal.

In neurogenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, and Parkinson’s, one of the underlying issues is a misfolding of proteins—something that can be very toxic to cells. Understanding what triggers that misfolding is the focus of research happening at Ursinus College, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is ensuring that important work continues.

NIH has awarded $418,000 to Professor and Chair of Biology Dale Cameron, a renewal of a grant first awarded in 2016. This is the second renewal, which means that Cameron’s work has had seven years of continuous funding and is assured of support through 2026.

“Hopefully, our work will help us to understand how cells navigate that delicate balance and achieve proper protein folding,” Cameron said.

Proteins perform many different functions in cells, but they must first fold into the correct three-dimensional structure, Cameron said. Misfolded proteins cannot carry out their normal functions and may sometimes even take on new, potentially toxic functions.

Prions are a unique class of misfolded proteins because they can induce other copies of the same protein to adopt the same misfolded shape, thus infectiously propagating their prion conformation. Prions are the cause of diseases like “mad cow” disease, scrapie in sheep, and chronic wasting disease in deer and elk.

Ensuring that each protein adopts the correct structure is an important challenge for cells.

“One of the aspects that our current work is aiming to look at is whether or not pauses during the synthesis of the prion proteins could impact the frequency with which they switch into these misfolded conformations,” Cameron said.

It’s something that hasn’t really been explored in the scientific community, so Cameron’s lab is at the forefront of the research.

They’re also researching specific “cellular quality control systems”—molecular “chaperones” that help prevent other proteins from misfolding. Cameron works with yeast cells, a versatile model system because it shares a lot of similarities with human cells, and he’s engineered the yeast cells to express human versions of those chaperones.

“We can now express human disease-associated misfolded proteins in our yeast system to more directly study human disease-associated processes,” he said.

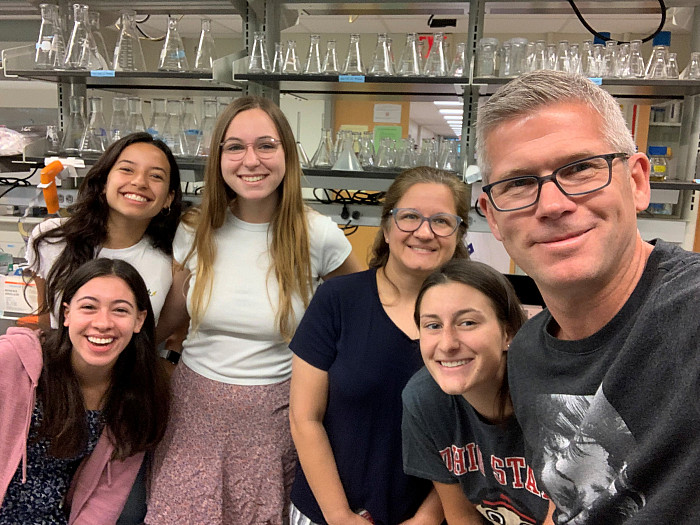

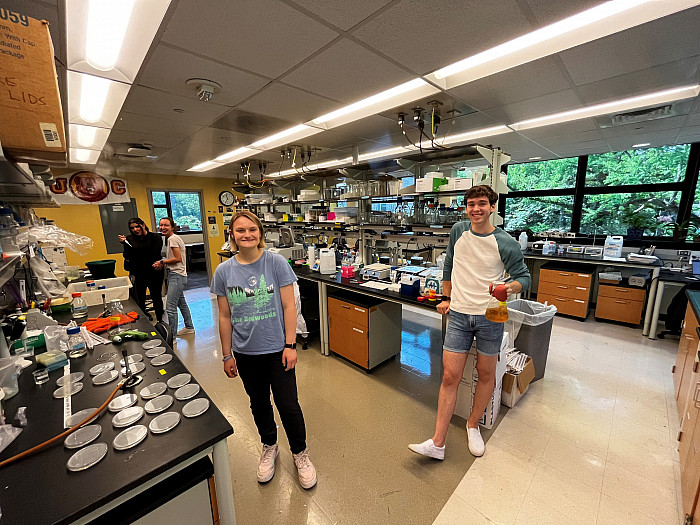

The NIH grant must be renewed every three years through a competitive application and peer review process. Thanks to the funding, student researchers have been able to present the work at national conferences in Chicago, Orlando, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C. Cameron and his students have also published articles on the research. The funding allows Cameron to purchase important supplies for the lab; and it supports his research associate, Dr. Christina Kelly, who has been instrumental in helping to train and mentor students in the lab and in ensuring the productivity of the research program.