What can historical pandemics teach us about COVID-19?

During the spring 2020 semester, junior and senior history majors grappled with the Black Death, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the four questions of the Ursinus Quest core curriculum. This is an excerpt from their research.

By Professor of History Susanna Throop and Morgana Olbrich ’20 Contributing writers: Tiffini Eckenrod ’20, Matthew Furgele ’21, Logan Mazullo ’20 and Andrew McSwiggan ’20

Most historians will urge you to avoid drawing oversimplified parallels between past and present. If we embrace oversimplified or generalized ideas of the past, we risk both misunderstanding the past and making flawed, misinformed decisions in the present. At the same time, one of the reasons why we are interested in the past is because of what it can potentially teach us. And as we all grapple with the COVID-19 pandemic, it is natural to ask—what can we learn from historical pandemics?

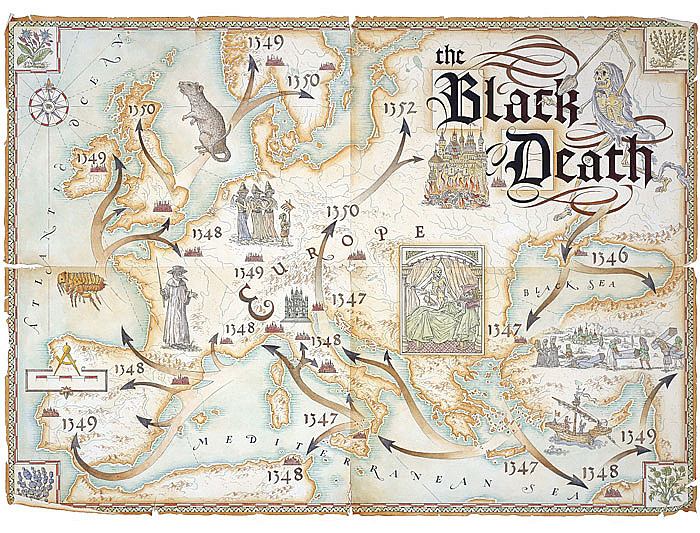

While COVID-19 is very different from the infamous 14th-century plague, it’s possible that studying the Black Death can teach us something about how to handle our current situation.

If we try to compare the Black Death and the current pandemic, we easily see some similarities. Above all, both outbreaks of disease have met the parameters to be considered a pandemic: a novel organism that is highly contagious and infectious, geographically widespread and fast-moving, with minimal population immunity [1].

In both cases, contributing factors include active global connections between human societies, climatic and environmental changes and human pursuit of resources from the natural world [2]. During both pandemics, people learned about the disease during and after its spread, and as a result of feelings of desperation, many sought easy answers and solutions. In particular, many sought a group of people who could be scapegoated, drawing upon existing prejudices to do so.

Similarly, in both pandemics, the impact of the disease depended on existing social, cultural, economic, and environmental factors [3]. In other words, dealing with a pandemic requires interdisciplinary perspectives. And both then and now, some individuals and communities went to extraordinary lengths to help each other.

So, what can we take from the study of the Black Death? There are six important ideas to keep in mind:

- Don’t panic. While we may think that we are doing what is best, panicked responses can actually put more people in danger than we realize.

- Be patient. Even in the 21st century, fully understanding COVID-19 will take time. We all want to know what is going on and what we should do, but spreading misinformation has the potential to harm others as well as ourselves.

- Don’t seek scapegoats. The pandemic should not and cannot be used as grounds for individuals to begin racist attacks or blame the sick for their illness.

- Address inequities. In the COVID-19 pandemic, already-marginalized people are suffering disproportionately or being left out of record-keeping altogether. The effects of social inequities and injustices are magnified in times of crisis.

- Remember to have hope and help each other. An act as simple as hoping and believing that an end is in sight may provide us all with a reason to keep fighting, even in a time filled with mass loss, suffering and uncertainty.

- Value interdisciplinarity, including the study of history. Historians are constantly revising and updating their knowledge of the past because they care urgently about the present and the future, and historians of disease and medicine have valuable insights to share.

Studying history requires the ongoing critical and comparative analysis of complex and potentially unreliable sources of information. Studying historical pandemics requires historians to work alongside experts in many other fields. Just as historical pandemics can only be understood through interdisciplinary perspectives, it will take the expertise of all the disciplines together to collectively understand and mitigate COVID-19.

Footnotes

- D.M. Morens, G.K. Folkers and A.S. Fauci, “What is a pandemic?” Journal of Infectious Diseases 200/7 (2009): 1018-21.

- For the Black Death, see Bruce Campbell, “Physical shocks, biological hazards, and human impacts: The crisis of the fourteenth century revisited,” in Le interazioni fra economia e ambiente biologico nell’Europe preindustriale. Secc. XIII-XVIII (Economic and biological interactions in pre-industrial Europe from the 13th to the 18th centuries), ed. S. Cavaciocchi (Prato: Istituto Internazionale di Storia Economica “F. Datini,” 2010), 13-32.

- Monica H. Green, “What happens when we expand the chronology and geography of plague’s history? (Or why Yersinia pestis is a good ‘model organism’ in these pandemic times),” Oxford Centre for Byzantine Research, University of Oxford, 16 March 2020.